The Königsberg Bridge Problem

In 10th grade, thanks to a change in curriculum by the Ministry of Education, I was able to replace my second foreign language classes with elective courses. I chose an Information Technologies and Software class, expecting it to be a purely coding-based course. However, I quickly discovered it would be much more than that ,especially since it was taught by one of my favorite teachers, who had previously taught math olympiad classes and worked in TÜBİTAK.

The class began with algorithm design basics. We explored simple shapes like squares and trapezoids, but in the context of what they meant for algorithms. Along with my closest friends (who coincidentally took the same class), we discussed and solved increasingly challenging problems, sometimes inspired by TÜBİTAK olympiad questions.

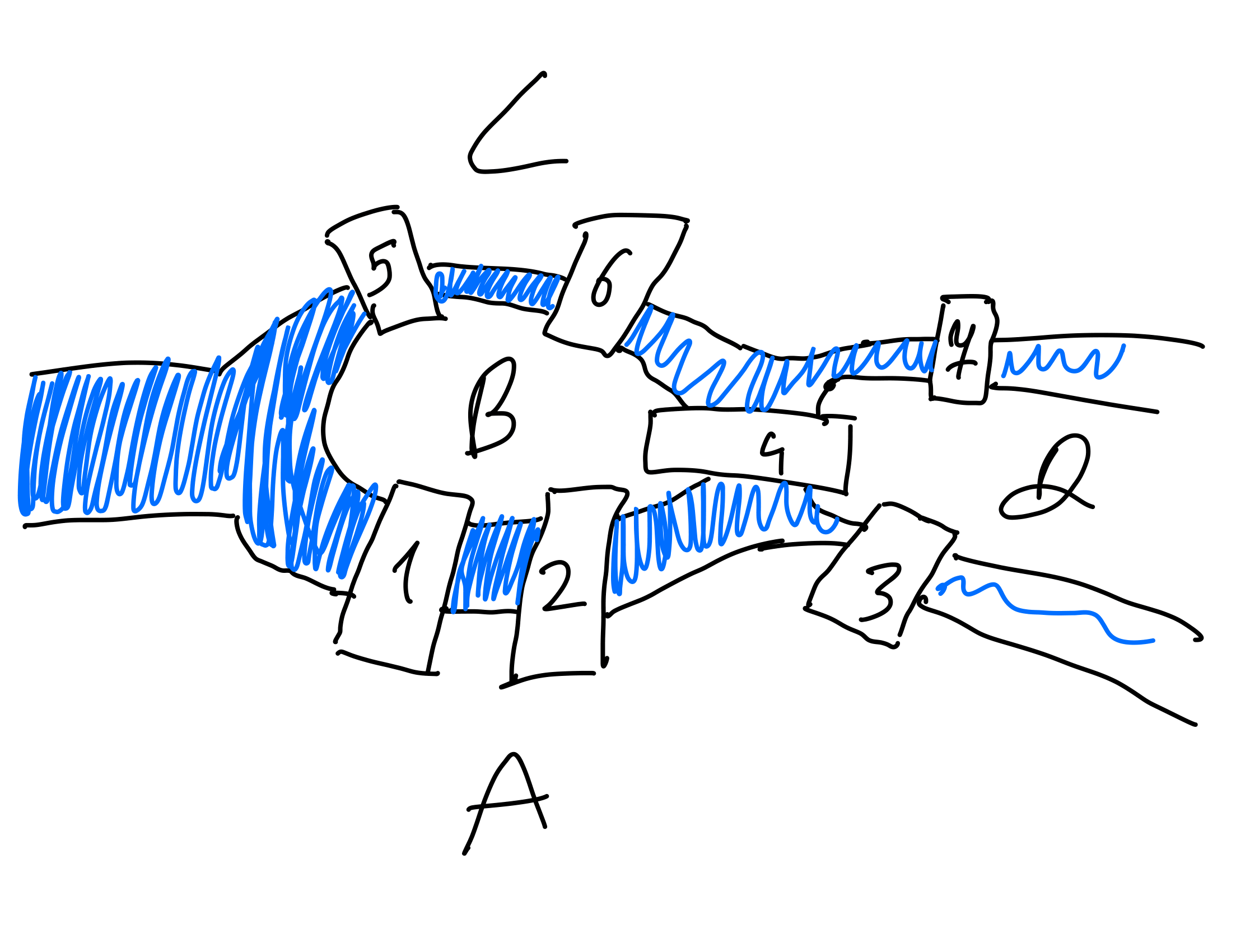

Everything changed when our teacher introduced the Königsberg Bridge Problem and Euler’s early ideas in graph theory. I had drawn the diagram you see above in my notes: the four landmasses are marked as A, B, C, D and the seven bridges connecting them are labeled 1–7.

Euler’s Question

The problem can be stated simply: Is it possible to walk through the city of Königsberg crossing each bridge exactly once? In other words, does a path exist that uses every edge of this graph exactly once?

Euler’s Solution

Euler proved that such a path (today called an Eulerian Path) is only possible if the graph has exactly 0 or 2 vertices of odd degree. In the Königsberg graph, all four landmasses have an odd number of bridges connected to them. Since more than two vertices have odd degree, the problem has no solution; it is impossible to cross each bridge exactly once.

This realization didn’t just solve a local puzzle, it gave birth to an entirely new field: graph theory. Concepts like Eulerian paths and circuits now form the foundation of algorithms used in network design, logistics, and computer science.

My Takeaway

For me, learning about this problem was one of the first times I truly felt the joy of mathematics and computer science merging. It showed me how abstract ideas can have powerful real world implications, from routing problems to data structures. The class went on to cover algorithms like Dijkstra, Prim, Kruskal, DFS, BFS, and even Polish notation calculators. But it was Euler’s bridges that made me realize: optimization, logic, and creativity can all live in the same problem.